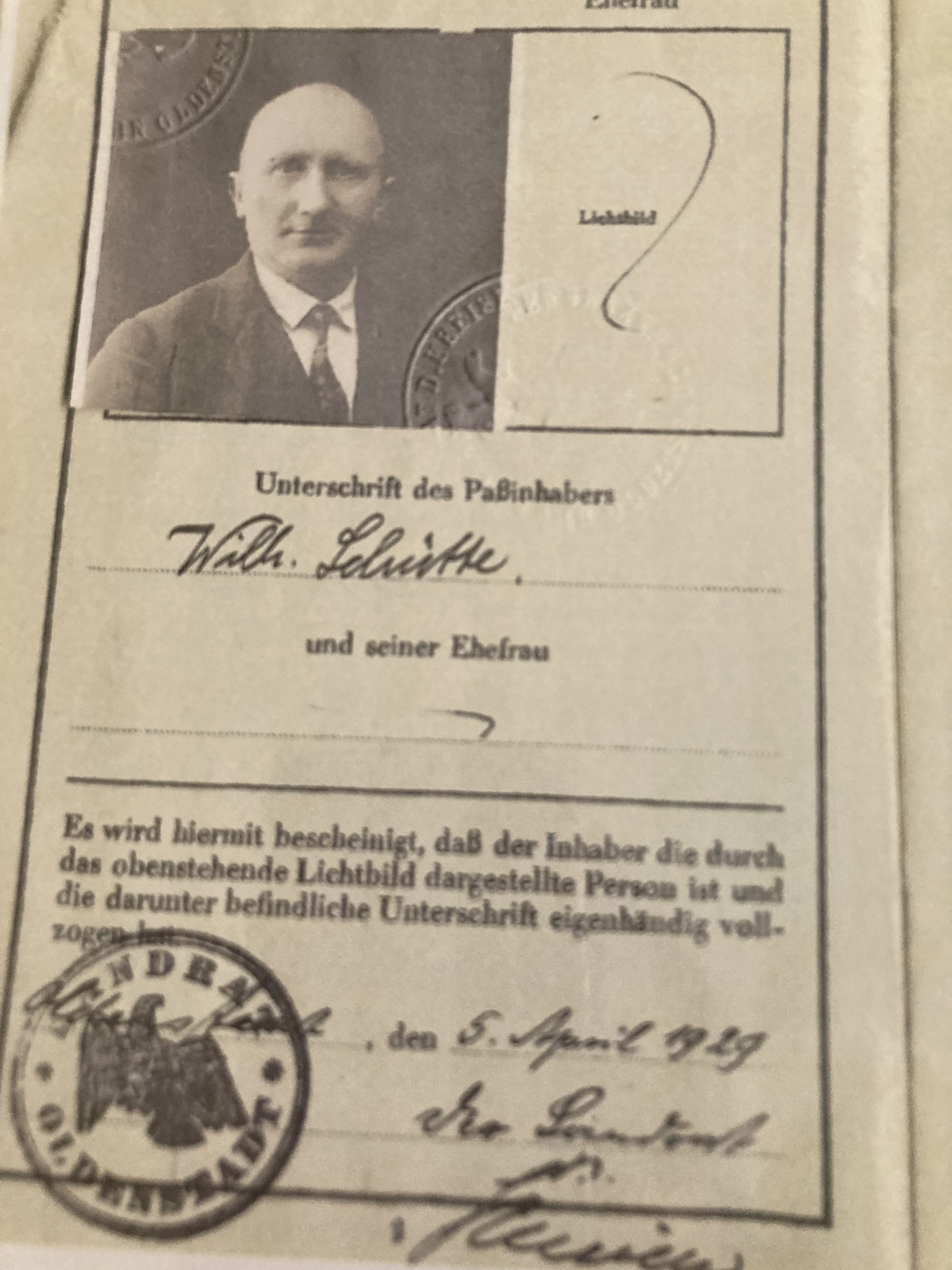

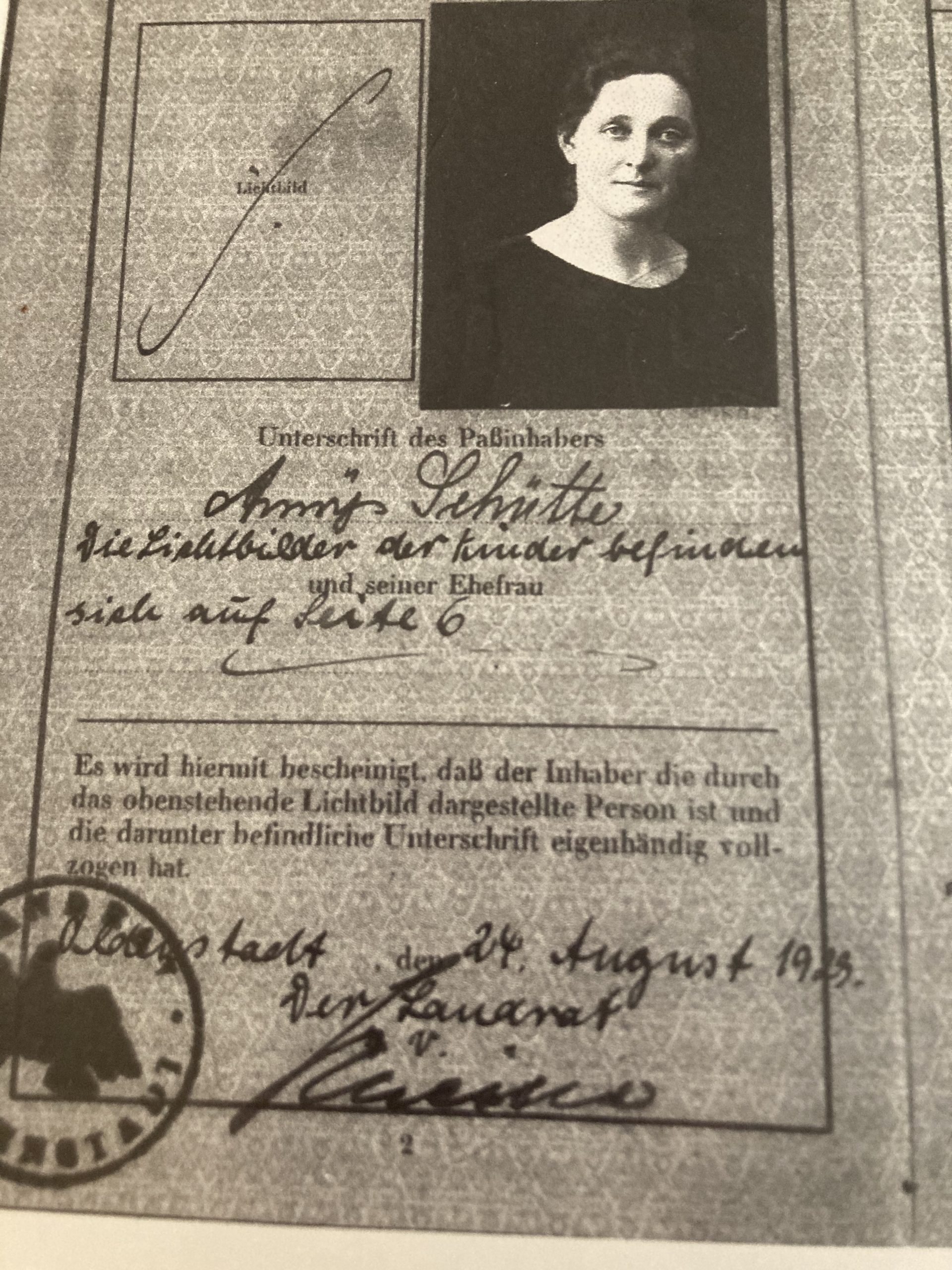

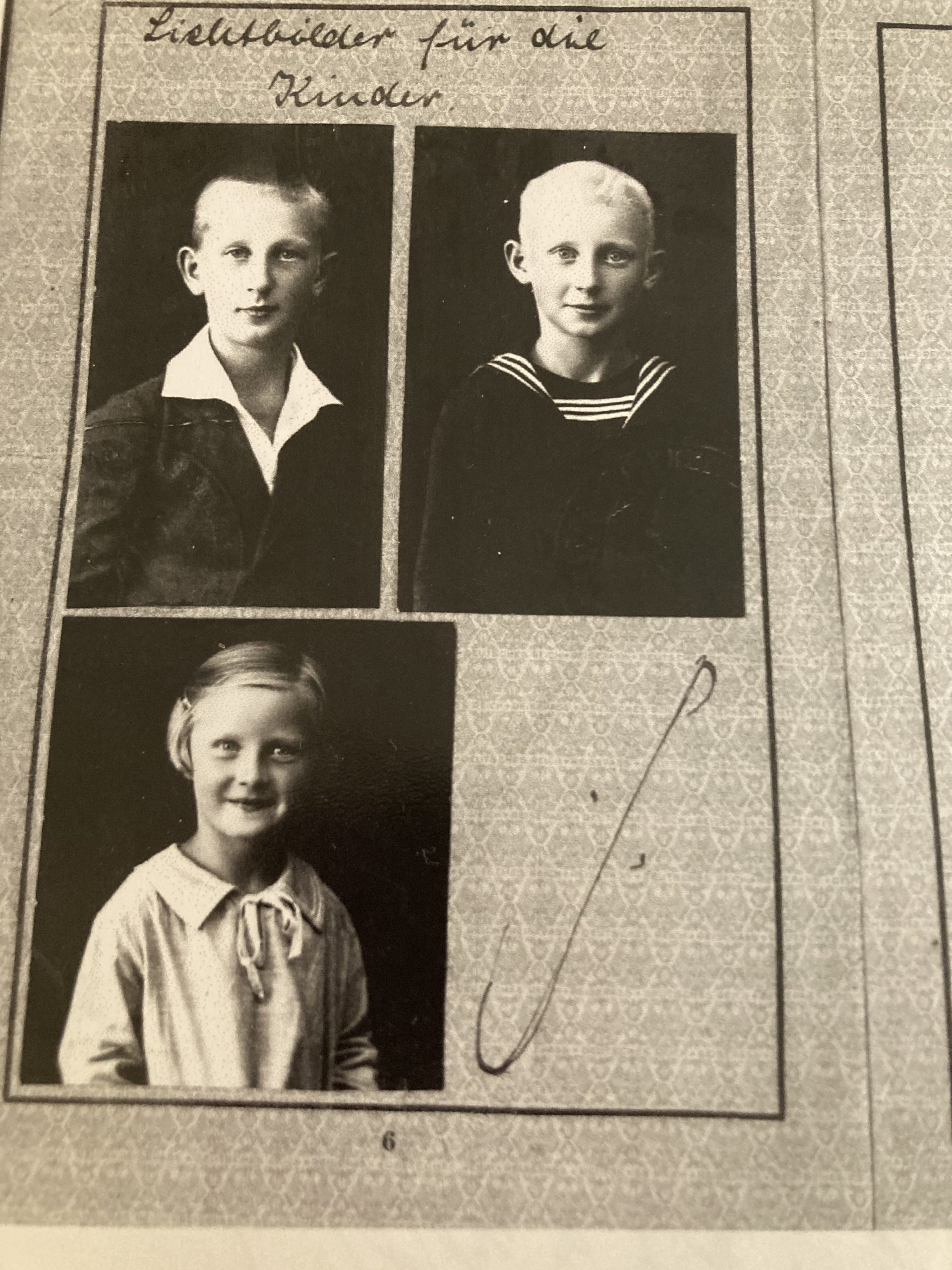

My paternal grandfather Wilhelm, from Uelzen in Northern Germany, came to America the way many immigrants did. A friend of his had already uprooted himself to find a better life here and implored my grandfather to do the same. With much cajoling he finally capitulated and ventured ahead of his family on May 31, 1929 on the Albert Ballin, a ship on the Hamburg-America Line. He would find suitable work in his occupation as carpenter/cabinet maker and send for his family when financially viable. That fall, on October 18, my grandmother Anny and my father Wilhelm (Bill, age eleven), along with his younger siblings Johann (Johnny, age nine) and Margarete (Margaret, age five), made the trek via the ship Reliance from Hamburg to a new world and new beginnings, after having sold all their belongings in Germany. They arrived at Ellis Island just in time for the advent of the stock market crash in 1929.

My grandparents were always referred to as Oma and Opa, the standard German reference. During the months before Opa’s wife and children came over, he was temporarily rooming with the friend who convinced him to make the journey. By the time his family arrived he had secured a three-room basement apartment for all of them at 145 East 15 Street, where a shared bathroom with other tenants brought the rent to ten dollars per week. After six months of an unsustainable situation of no light or windows, uncirculated stale air, unrelenting noise, and suffocating lack of space for five people, they relocated.

They moved by horse and wagon to Eighteenth Street on the east side. There they graduated from the previous basement level to the fifth floor, the top floor, where there were now five rooms, windows and more air, and a manageable family bathroom. The rent at the new location was forty-two dollars per month, plus gas and electricity. Here they remained a year and a half. Considering that Oma and Opa, my father and his siblings, plus their grandparents were all raised together in a small town in Germany surrounded by farm animals, gardens, and the old-fashioned harvest of each, it was difficult making the adjustment to the cacophony and hustle and bustle of a claustrophobic city life. My father found it particularly stressful. He missed the open space, fresh air, and quieter atmosphere of the country environment. That was undoubtedly true for Oma and Opa, as well.

Opa had started hearing more about Brooklyn from another friend from the Old Country. Carl Obst and his family lived on the first floor of a building near Fourteenth Street in Brooklyn and were quite content there. He kept saying it was the borough of parks and churches. The schools and availability of outdoor activities added to the appeal. After checking it out for himself and feeling an uplifting difference, Opa and the family were ultimately convinced that Brooklyn was the place to live and thrive. In 1931, when Oma was thirty-seven and Opa was forty-three, they all moved to the third floor of 14 Stewart Street, the top floor. The open space arrangement within the apartment was different from anything the Uelzen family had previously encountered. There was also a community basement for the varied tenants. It came in handy, particularly during Prohibition in the 1930s. Within that subterranean protection the Italians made wine, the Germans made beer and whiskey, and the English and Irish made their own brand of brews.

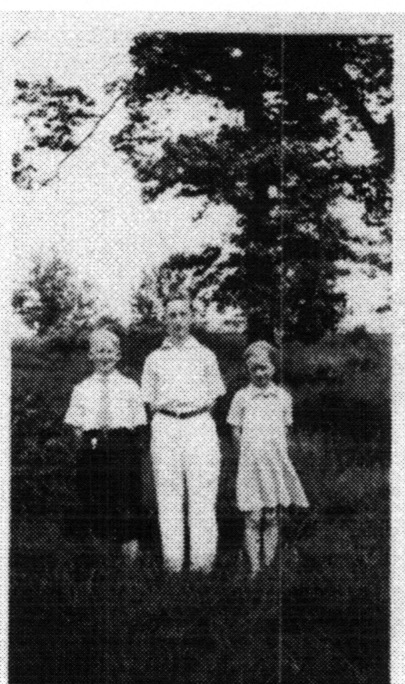

1932 Johnny, Bill, and Margaret. Highland Park, Brooklyn.

The rent at the time was twenty dollars per month, under the management of a landlord named Bescher. In 1954, when a Puerto Rican landlord converted to heating with oil, the rent was raised to fifty dollars per month but never changed again until Oma and Opa went into the Ivy Nursing Home in New Jersey. They lived at their Brooklyn address for thirty-five years, until 1966, when my brother and I graduated from high school in NJ. Having visited them frequently, the memory of that apartment will remain with me as long as I live.

Ascending the brownstone steps of 14 Stewart Street and trudging up three flights of stairs brought one to the front door of Oma and Opa’s railroad flat in Brooklyn. Upon entering, the inner sanctum revealed itself straightaway. The open dining area, with a dark wood oval table and curved glass wooden china closet set against the wall, presented the initial visual greeting. Welcoming aromas wafted from the kitchen area to the left; those from the old-fashioned coffee grinder, perched prominently on a shelf, were particularly inviting, suggesting a forthcoming Kaffeeklatsch with Oma’s signature Butterkuchen. It was not to be missed. When she cut a round loaf of robust German bread, she would brace it against her chest with one arm and slice TOWARD HER with a sharp knife in the other hand. Though I winced every time, it was child’s play to her, and the slices were expertly even. She had an easy laugh and impish twinkle in her eye, particularly on her home turf. It was clear that the kitchen and dining area were the heart and hearth of the living space.

The kitchen, being at one end of the apartment, had two windows directly facing the above-ground BMT railway and laundry lines. I would often love to sit by one of the windows and watch and listen to the trains come and go. It was a novel experience for me to absorb such a city experience, having lived until that time only in the countryside. Laundry lines, however, were a familiar site for me, since that was how clothes and sheets were dried where we lived. At the opposite end of the apartment was the living room, also with two windows, facing the street and other brownstone apartment buildings. This was where Opa liked to hold forth, while Oma held her own in the kitchen. He liked to pontificate forthrightly, yet harmlessly on subjects surrounding stocks, economics, and the cost of living. This was mostly in German, since he held tightly to his heritage. Opa had an unusual greeting for us kids when we visited, as his regular gesture of love. Instead of a grandfatherly hug that many would consider natural and normal, he would give us a five-dollar bill and a handshake. Though I understood his loving intent, it wasn’t until years later that I realized how bizarre it could seem to others. In his neck of the woods, he wasn’t raised with the idea of men expressing much outward emotion.

In venturing from one end of the abode to the other there were no doors or detours to impede the route. Walking past the dining area along the creaky, linoleum type flooring brought one to the main “bedroom,” then the tiny “bedroom,” both before arriving at the living room. The term “room” appearing anywhere here is used loosely, of course. With the entire living space as one continuing hallway with designated areas, nothing was closed off, except for the tiny “bedroom.” It had some semblance of a doorlike entry from the living room and apparently was Oma’s hideaway sleep space. In a seemingly mystical manner during my early youth, I discerned that Opa slept in the larger sleep area. The double bed, past the dining area, was against the wall lengthwise, allowing sufficient hallway space to traverse the apartment. It was always neat and tidy with its chenille cover, encasing two pillows. Perhaps Oma varied her sleep site from time to time.

Lest one deduce the apartment had no bathroom, I saved the actual ROOM for last. It was located off the kitchen behind a dependable door, with a key, no less. It included the basics of the time: a wood-handled pull chain toilet with white ceramic water tank high above it, a small hot and cold fixtured sink, and a large claw foot tub. The tub remains memorable to me because I once encountered a living carp swimming laps in it, ostensibly its final exercise before being lured toward the idea of dinner.

This is the very same apartment where my mother Karola first arrived from Germany, first met her in-laws, and lived with them and her new husband Bill temporarily for two and a half months, from December 28, 1947 until March 15, 1948. After that, life for the newlyweds, Karola and Bill, commenced in earnest on their own terms, starting on a dairy farm in Lincroft, NJ. Once Oma and Opa became grandparents, visits started flowing between 14 Stewart Street and wherever we were living at the time. They finally had the best of both worlds, the city and the country.